Forced Labor in the Third Reich – Part VI

The Personal Account of a Polish Slave Laborer — March 2019

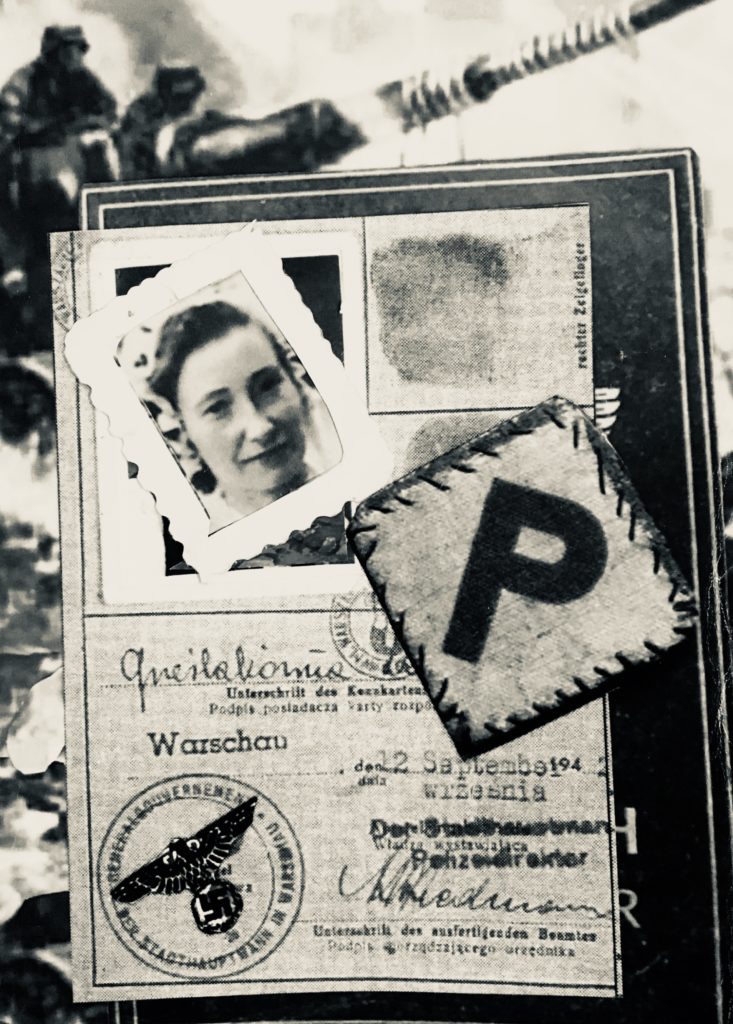

Katherine Graczyk, a Polish Catholic, was captured by the SS and shipped to Germany. She shared her story with author Catherine Hamilton*

by Catherine Hamilton

—

PART VI

Life was very difficult at Wildflecken Displaced Persons (DP) Camp, as was the case in DP camps all across Germany. Every day more people at Wildflecken died due to poor health caused by starvation during their captivity as slave laborers or as prisoners. We lacked adequate food and medical supplies. Many of the children had rickets.

Hand-drawn map to Wildflecken

Hand-drawn map to Wildflecken

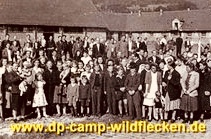

Camp yard at Wildflecken

Camp yard at Wildflecken

We knew the dangers of returning to Communist Poland—deportation to Siberian camps, or imprisonment. No matter how much we longed for home, we had to think of our child’s future.

Frank and I were thankful to be alive, thankful that at last we could send letters to our families back home. I wrote to my mother and told her everything. How I’d survived the war. That I was now living in a DP camp. About Frank and me and our marriage, and her newborn grandson. I sent her my favorite wedding photograph. To my sisters, Sophie and Anna, I wrote every detail about their sweet little nephew, Kazimierz. I didn’t tell them the hardships we were suffering.

Katherine and Frank’s favorite wedding picture

Katherine and Frank’s favorite wedding picture

A year passed at Wildflecken and I didn’t hear back from my family. I felt frantic that something terrible had happened. Did the communists even deliver our mail? I told myself they hadn’t delivered my letters. Every month I sent a letter, never giving up hope, praying they had survived.

In late December, 1947, our one-year-old son fell ill with a bad influenza. He had diarrhea and was vomiting. I had nothing to give him—no medicine at all. And we had only a quart of milk and some bread, which he wouldn’t eat.

“We have to take Kazimeirz to the hospital,” I told Frank. He agreed. We bundled Kazimeirz in blankets and rushed there on foot.

We were surprised when the clerk working at the front desk of the hospital said, “This hospital is not for Poles.” Her tone was menacing. “Go back to your camp.”

But I refused to leave and approached one of the nurses, asking her to help us. She nodded and asked, “What’s wrong with the child?”

“He won’t eat anything. He has a fever,” I said. “I didn’t know what else to do. Can you help him?”

She nodded again. “We’ll need to keep him overnight. You should come back tomorrow after the doctor sees him.” She took him from my arms, saying I shouldn’t worry. To get some rest and she would see me tomorrow. I agreed and the next day, I went back to the hospital as I had promised.

The young nurse who greeted me in the waiting room said, “I’m sorry. You’re mistaken; your son isn’t here. We don’t have Polish babies.”

“I brought him here yesterday,” I said, feeling sudden panic. “The nurse that was here said she’d help him. She told me to come back today. Do you think I would lie about my child? He’s here, somewhere!”

“That’s impossible!” the nurse insisted.

“But he IS here!” I got so upset I started speaking in Polish. “Masz moje Dziecko! Pozwól mi zobaczyć moje dziecko!” I cried. (You have my baby! Let me see my child!)

“I can’t understand you!” She turned away and walked up the hall, returning with another nurse, an older woman, clearly the one in charge. “What’s the problem here?” the older woman asked.

“She’s insisting we have her baby,” the young nurse complained, gesturing toward me. “I told her we don’t have any Polish children.”

“There are a few Polish children here. What’s the child’s name?” the older nurse asked.

“His name is Kazimierz Graczyk.”

She looked through some papers. “He’s here. But I’m sorry to say you can’t see him. He’s been placed on quarantine.”

“But I’m his mother.”

“There’s nothing I can do. It’s policy. You should go now. Try back tomorrow.”

I couldn’t leave him. I pretended to go, but I turned around and sneaked into the other hallway. Carefully, I slipped past a nurse’s station unnoticed. I found Kazimeirz in a tiny bed. He looked at me but didn’t move. He had been walking since he was nine months old—why didn’t he move? I don’t know if he recognized me. He was licking his lips, smacking them as if he were very thirsty. I reached for him to pick him up, but a nurse spotted me. She pushed me out of the room. “I’m his mother!” I screamed.

The hospital police came and dragged me away. All the while I cried, “I’m his mother! I’m his mother!”

The next day, New Year’s Day, 1948, the hospital telephoned the camp office before daybreak. A British officer brought me the message. My Kazimierz had died.

My heart still breaks when I think of him dying there alone. Plagued, as you can imagine, by untold guilt that I did the wrong thing taking him to that hospital. Haunted by questions: Did they try to help him? Did they give him fluids? Did they just let him die?

I later found out that not one Polish child came out of that hospital alive that year. Hitler was dead, but the Nazi ideology of the super-race continued to take the lives of Polish people trapped inside that country. I believe my firstborn son was one of those people. It wasn’t until a doctor from the United States was assigned to the hospital that equal care was administered to Polish adults and children. Poles could finally go to the hospital near camp Wildflecken without fear. It was because of that doctor that Frank and I decided to emigrate to America.

While we waited to get our papers from the United States, my daughter Stella was born.

Frank with baby Stella

Frank with baby Stella

Katherine, Frank, and Stella at Wildflecken DP camp

Katherine, Frank, and Stella at Wildflecken DP camp

Thankfully, by that time, life had improved at Wildflecken. My Stella was a healthy happy, baby, and the three of us immigrated safely to the U.S. in 1951. We celebrated that my brother Antony Ponczocha, who had also survived forced-labor camps and had recently married Janina, a Polish woman he met during his captivity in Germany, had received immigration papers for Australia.

DP’s waiting for immigrations papers

DP’s waiting for immigrations papers

When our ship docked at the New York Harbor, we were famished. We walked with little Stella to the first restaurant we could find to get something to eat. But neither Frank nor I spoke a word of English. We stared at the menu and saw SOUP. This word looked very similar to ZUPA (soup in Polish). So we asked for “Zupa.” The waitress understood. Soup was the only thing we had to eat for days! We quickly got to work on our English lessons!

Six years after the war’s end, at last, we were free!

We settled in Denver, Colorado, and there our third child, Richard, was born. Frank worked as a butcher in a meat packing plant, while I managed the home and cared for the children.

Katherine Graczyk in Denver with son Richard

Katherine Graczyk in Denver with son Richard

There were so many other Polish immigrants in Denver that very soon the center of our family life was Saint Joseph’s Polish Catholic Church and school. Because of the Communist occupation of Poland we had no hope of returning to visit family back home, although we tried many times. We weren’t allowed to set foot in Poland, now that we’d come to the United States of America. So I wasted no time trying to contact my family again by mail. I was so worried about my sisters and my mother and my cousins. I hadn’t received even one piece of mail from any of them in more than twelve years. And because there were no telephones in my village, Lipkie Harta, I had to rely on letters.

Saint Joseph Polish Catholic Church

Saint Joseph Polish Catholic Church

I sent my first letter from America. Then the second. When I received my first letter from home, I wept for joy. The floodgates were open and no end of letters were exchanged over the years. From their letters I learned what happened to the rest of my family during the war. Sophie and Anna and Mother had survived the Nazi occupation! Now they found themselves under the Communist occupation. They couldn’t travel outside the “Iron Curtain.” They had no choice but to remain in Poland after WWII. My first cousin Maturz Ponczocha died in a Nazi prison camp. My aunt and uncle, Maturz’s parents, were arrested by the Russians as the Red Army invaded Eastern Poland. They died in Stalin’s Siberian labor camps. My cousin Sophie survived the Siberian forced labor and returned to Poland, but her farmland was never returned to her. It had been confiscated by the communists. Not until 1972, after my mother’s death did the Russians let me return to Poland for her funeral.

Frank and I always felt extremely blessed to have survived the slave labor camps and the prisons of Nazi Germany. And despite our suffering the loss of our firstborn son, we made a good life for ourselves in the United States.

Now with my story down on paper, after spending years wrestling with the enemy that haunted my bones—that woke me up at night, living with nightmares and bad memories and regrets… Now that I can release the dove and find peace, I have one more thing to say: I hope my story will enlighten people in the free world and that they will know what happened to 1.5 million ethnic Poles during the Nazi occupation of Europe.

THE END

Frank Graczyk died in 1986. Katherine Graczyk passed away on Monday, June 14, 2010 in Denver, Colorado.

Note

- I am a freelance writer in Beaverton, Oregon and recorded Katherine Graczyk’s story during a series of interviews. I am honored to write the first-person account of her experiences; Katherine Graczyk and I were cousins. Part of Katherine’s story was also published in the anthology FORGOTTEN SURVIVORS, edited by Dr. Richard Lukas.

AFTERWARD

I met my cousin Katherine for the first time in 1997 at her home in Denver, Colorado, after listening to an audio tape she had made for my father. In this recording, I learned that she was kidnapped from her village in Poland and survived slavery in Germany. I wanted to know more. And there began my journey with Katherine Graczyk. We had a series of face-to-face interviews and untold telephone conversations as Katherine detailed the events of her captivity in Germany. Her only request was that I one day write it down.

This particular story would not let me rest until I’d exhausted every resource at my disposal. There were others who had shared my cousin’s fate, but why hadn’t I heard of Hitler’s slave-labor campaign targeting Polish-Catholic young people? And how many others were there?

I found data about thousands of Polish people forced into slave labor during the Second World War. By August 1944, 1.7 million Poles had been forced into slave labor by Nazi Germany, nearly half of them women. Many did not survive. Katherine was one of the lucky ones.

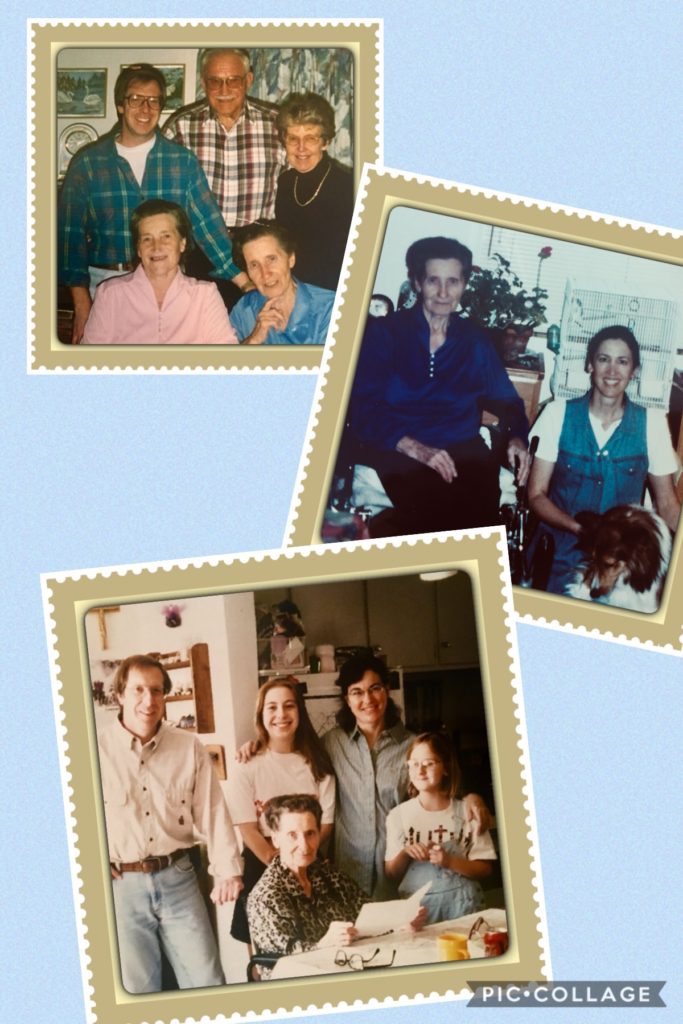

Clockwise from top left:

Photo of my parents when they first met Katherine and her sister in the 1990’s; TOP LEFT ROW: Richard Graczyk (Katherine’s son), Joseph Ponczocha (my father, Katherine’s cousin), Jeanne Ponczocha (my mother). BOTTOM ROW: Anna Ponczocha (Katherine’s sister, who had come to visit from Poland), Katherine Graczyk.

A photo of Katherine and me in Denver, 1997, with the beloved family collie.

Family photo of Richard Graczyk (Katherine’s son), his daughter Katie, wife Annie, and daughter Melony. Katherine is seated at the table looking over a map she had drawn for me of our family’s village in Poland.

Thank you for reading my blog series. Follow me on Facebook for upcoming events and publications.

Catherine

An excellent profile of Polish Solidarity leader Anna Walentynowicz. Catherine A. Hamilton shows an impressive grasp of Polish history and ability to present it with objectivity and fairness. I was in charge of the Voice of America (VOA) Polish Service when these historic events were taking place. Ms. Hamilton captured their significance while focusing on a woman whose courage inspired others to start with her a peaceful revolution against communism and Soviet domination of Poland.

Thank you for your comments Ted! Anna Walentynowicz is a great inspiration. And the subjects of the Katyn massacre and the 2010 plane crash are of particular interest to me. In fact, I’m working on a novel that juxtaposes these events.

I like the report

Thanks! I’m so glad you liked my article!

This is a heartbreaking story, one of hundreds of thousands stories of Polish women who were tortured, murdered, worked and starved to death in German and Soviet slave labor camps during World War II. Many of the mothers had lost their children to starvation and disease, or their children were taken away from them and some were never found. The death rate among children was especially high in German concentration camps and in the Soviet Gulag. Americans know almost nothing about this 20th century slavery and genocide. Catherine A. Hamilton’s publication of Katherine Graczyk’s moving memoir helps to bring much needed attention to this hidden and forgotten history. We also need to know more about Polish women who went thorough the Soviet prisons and slave labor camps. As someone who is studying the history of Soviet deportations, I find Catherine H. Hamilton’s blog extremely useful in showing how the two murderous totalitarianisms used similar methods to exploit and exterminate Poles, Jews and other groups considered as subhumans or as “enemies of the state.”

Thank you for the exceptional blog review, Ted! Your summary of this series serves as a perfect synopsis for future readers! Obviously, you are a scholar on the subject of WWII! Thanks again for reading my series and supporting my efforts to get the truth out about what happened to the Polish Catholic during WWII.

What a beautiful and knowledgeable review of Catherine’s series documenting the fate of enslaved Polish Catholic girls and women—along with those of other devalued ethnicities and also their men and their children—at the hands of the Nazi’s. And you’re right about the Soviet Gulag. I look forward to your further exposition of what happened with the equivalent Soviet-communist ensalvement and genocide of Catholic Poles. N. Gregory Hamilton, M.D.

Thanks so much for the comments and your ongoing support for this project, Gregory!

A fascinating story. As a student of twentieth-century history, I am grateful for your research and was excited to learn about this element of the period surrounding WWII.

Many thanks for reading my series and helping me bring this story to light! It is near and dear to my heart, as well as being historically relavent!

Such and important part of history unknown to so many!!! Thank you for recording this account by a primary resource. So important.

Thanks so much for following my series! And thank you for the support on getting this untold story out there!